Less is more for health and happiness

- …

Less is more for health and happiness

- …

What Is Thyroid Eye Disease?

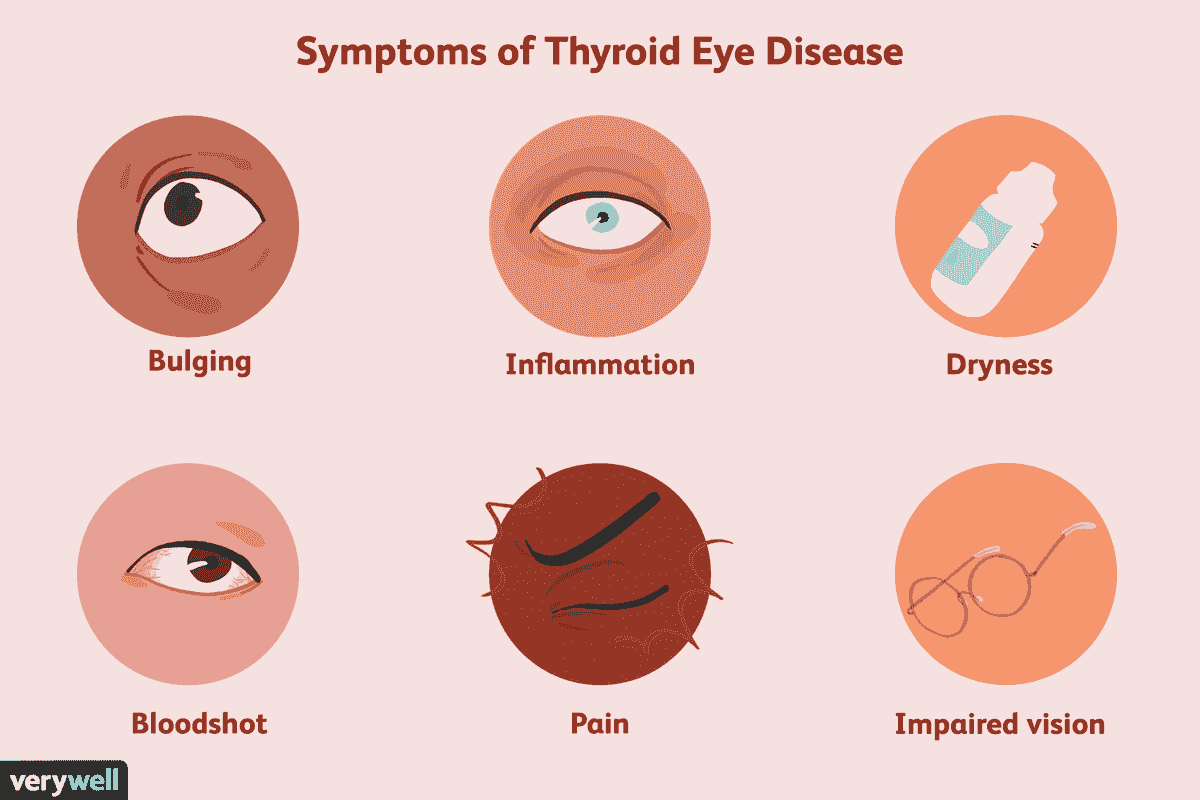

TED stands for Thyroid Eye Disease, which is an autoimmune condition often associated with Graves' disease. It affects the tissues around the eyes, causing inflammation, swelling, and sometimes symptoms like bulging eyes, double vision, and discomfort. TED can significantly impact a person's quality of life, both physically and emotionally.

It's important to recognize TED early and manage it with a multidisciplinary approach, including endocrinologists and ophthalmologists. Achieving normal thyroid levels (euthyroidism) is a key part of treatment, and guidelines like those from EUGOGO help tailor care based on the severity and activity of the disease.

Symptoms

- Bulging eyes (proptosis)

- Eye irritation

- Swollen and inflamed eyelids (blepharitis)

- Dry eyes or teary eyes

- Frequent blinking

- Light sensitivity (photophobia)

- Eye pain and headaches

- Difficulty moving your eyes

- Double vision (diplopia)

Causes/Risk factors

- Autoimmune diseases

- Graves' diseases

- TSHR stimulating autoantibodies

- Abnormal thyroid hormone levels

- Radioiodine therapy

- Smoke

- Characteristics of high-risk thyroid eye disease patients

Managment

- Eye drops

- Selenium supplements

- Eyeglasses with prisms

- Thionamides

- Corticosteroids

- Teprotumumab

- Radiation therapy

- Clinical trials

5 Effective Ways to Reduce Stress

Thoughts, musings, and ruminations

March 1, 2026 · science,artRead more...The sun shone brightly over the seaside dock, and a gentle breeze carried the faint scent of...February 7, 2026 · scienceRead more...1. Eyes "bulging out" – The eyeball protrudes from its socket, causing the thyroid gland to...January 31, 2026 · scienceRead more...I. First, a review: What are autoantibodies against TSH receptors? Remember in Graves'...January 24, 2026 · scienceRead more...I. First, let's understand: What is Graves' disease? Our bodies have an "immune system...January 17, 2026 · scienceRead more...Let's use the analogy of the thyroid hormone factory again, explaining the relationship between...January 10, 2026 · scienceRead more...1. Thyroid-stimulatinghormone (TSH): The "messenger" of the thyroid gland. It resides in a small...January 3, 2026 · scienceRead more...Thyroid eye disease is an autoimmune disorderclosely related to Graves' disease. It causes...December 12, 2025 · clinical trials,scienceRead more...Background 1.1 Thyroid Eye Disease (TED) Thyroid eye disease (TED) is a disabling condition...October 30, 2025 · mental healthRead more...Meaning in life, a global belief that one’s life has meaning and is significant, has long been...October 30, 2025 · mental healthRead more...Positive thinking is looking at the brighter side of situations, making a person constructive &...October 30, 2025 · mental healthRead more...Flourishing—a state of optimal mental health—has been linked to a host of benefits for the...Hello & Welcome

Add a subtitle here

Managing TED

What are nonsystemic treatment or lifestyle advices for TED?

Will lubricating eye drops be helpful?

What are the artificial tears?

What are the Fresnel press-on prisms?

Should patients stop smoking or avoid second-hand smoke exposure immediately?

Is ‘watchful monitoring’ strategy acceptable for moderate-to-severe TED patients?

What's the percentage of spontaneous disease inactivation and improvement?

What's the urgent treatment for sight-threatening TED?

What are the goals of the treatments for the active phase of TED?

What are the immunomodulatory treatments?

What's the mechanism of action of immunomodulatory therapy?

What are major adverse effects of immunomodulatory therapy?

Is immunomodulatory therapy efficient?

What's the referral guidance for patients with TED?

When should carry out surgical treatment for TED?

What's the medical therapy for mild TED?

What's the therapy to calm down orbital inflammation?

What's the second-line immunosuppressive agents?

Which type of surgery is recommended for mild TED?

What are available treatments for moderate-to-severe active TED ?

What's the risk factors for TED?

When are glucocorticoids used for TED?

What's the difference between OGC and IVGC?

What's the standarized dosing for GC?

What are adverse events (AEs) in relation to GC?

Which kind of patients are not suitable for GC treatment (Contraindications)?

What are adverse effects of medical therapy for thyroid eye disease?

How much is the drug cost for TED?

What are the impact of drug on vaccinations?

What are therapies for patients unresponsive or intolerant to GC?

What are the emergying therapies recently approved?

What are the emergying therapies in clinical trail stages?

How to find suitable clinical trial?

What outcome should patient expect for antcipating clinical trials?

Thyroid Eye Disease (TED)

What is Thyroid Eye Disease?

What's the common symptoms of TED?

What does double vision (diplopia) mean?

What do bulging eyes (proptosis) mean?

What does periorbital oedema and chemosis mean?

What does strabismus mean?

Who Should Get Tested for TED?

What's the difference between Graves’ Disease and Thyroid Eye disease?

What's the Tests for Thyroid Eye Disease ?

What's the Clinical Eye Exam of Thyroid Eye disease?

What's the Visual Acuity Test for Thyroid Eye disease?

What's the Exophthalmometry?

What's the Orbital Imaging (CT or MRI Scans)?

What's the Blood Tests for Thyroid Function?

How to Prepare for Testing of TED?

What Do the Results of TED Mean?

When to Retest or Monitor TED?

What does eye irritation or dryness mean?

What does excessive tearing or watery eyes mean?

Why is there redness or swelling around the eyes?

What is slit-lamp evaluation?

What are the assessment scores or systems for TED?

What does VISA (Vision, Inflammation, Strabismus, Appearance) mean?

What does Clinical Activity Score (CAS) mean?

What is GO-QOL (Graves’ Ophthalmopathy Quality of Life) questionnaire?

What is EUGOGO Classificationare of TED?

What is Modified NOSPECS Classification of TED?

Passion

Use a text section to describe your values, show more info, summarize a topic, or tell a story. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore.

Independence

Use a text section to describe your values, show more info, summarize a topic, or tell a story. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore.

Happiness

Use a text section to describe your values, show more info, summarize a topic, or tell a story. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore.

Happiness

Use a text section to describe your values, show more info, summarize a topic, or tell a story. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore.

FAQs

Add a subtitle here

What is the FAQ section?

What is Strikingly?

How do I create a website?

Thyroid eye disease is a complex inflammatory disorder

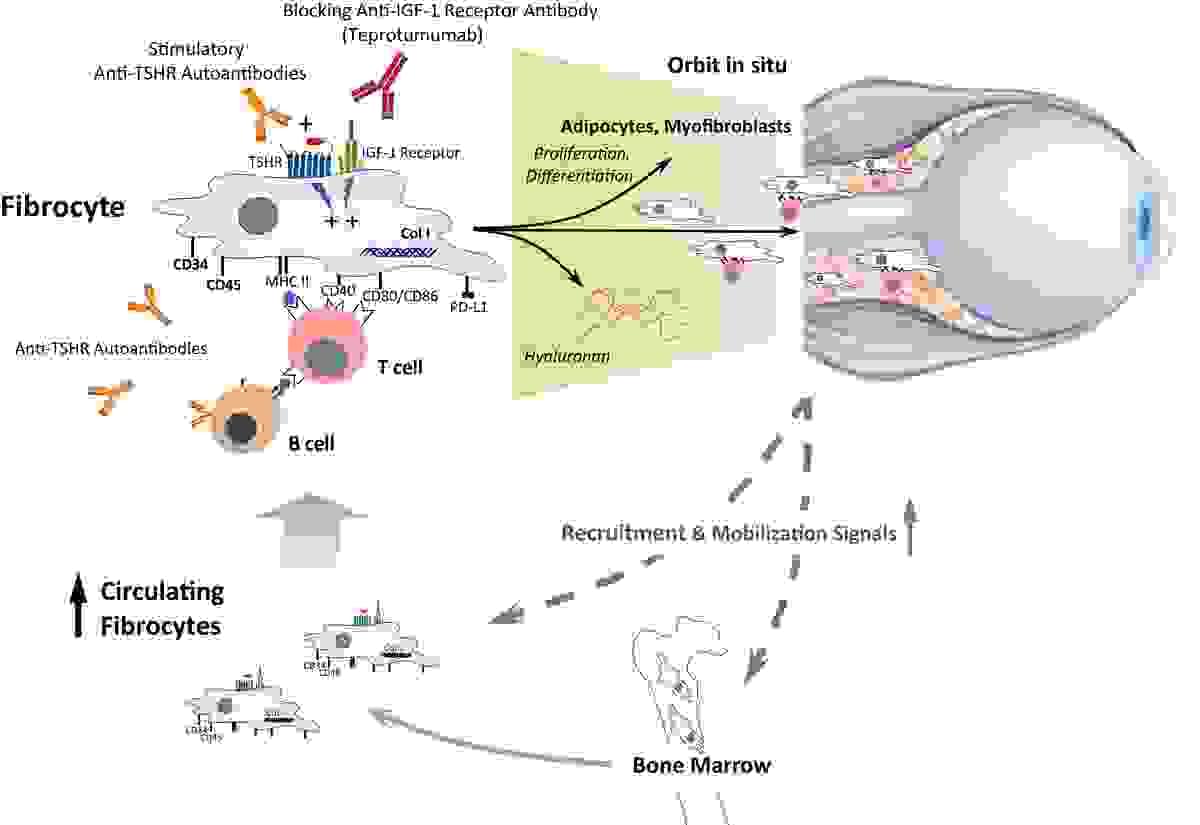

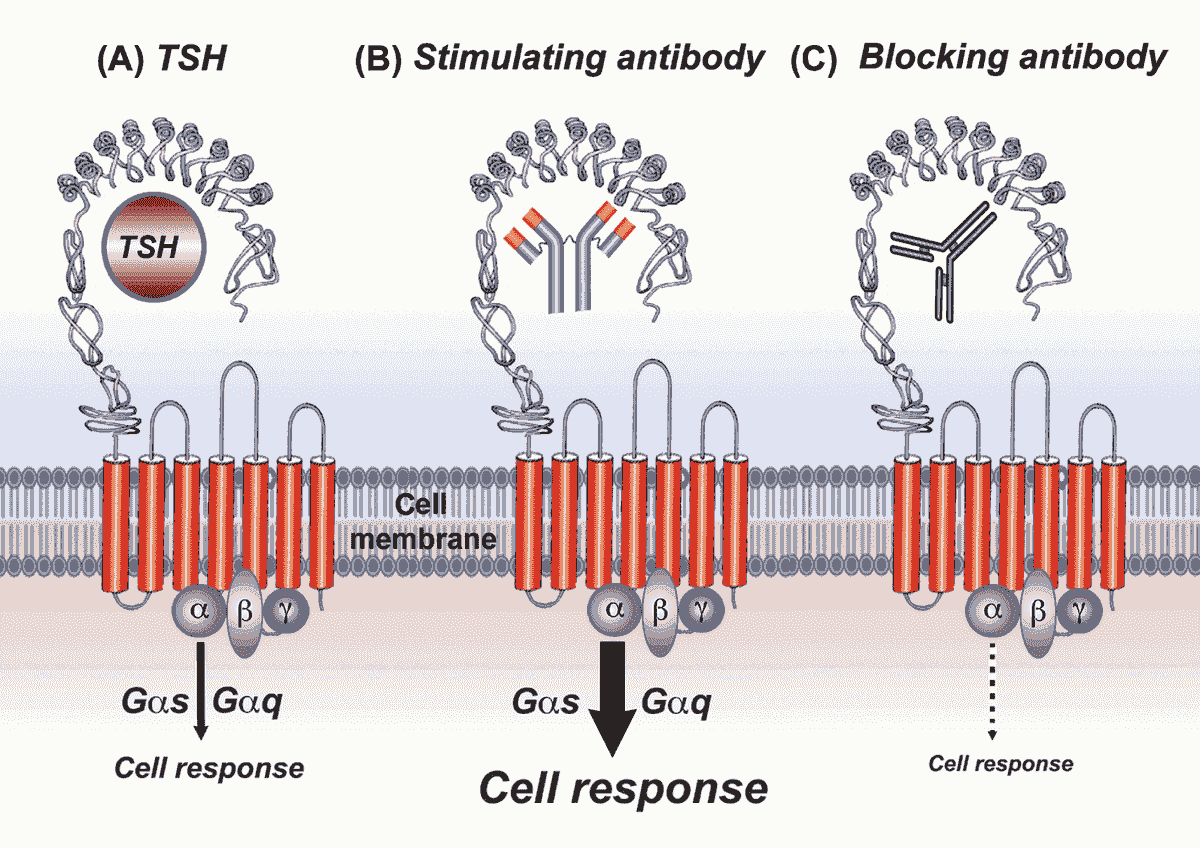

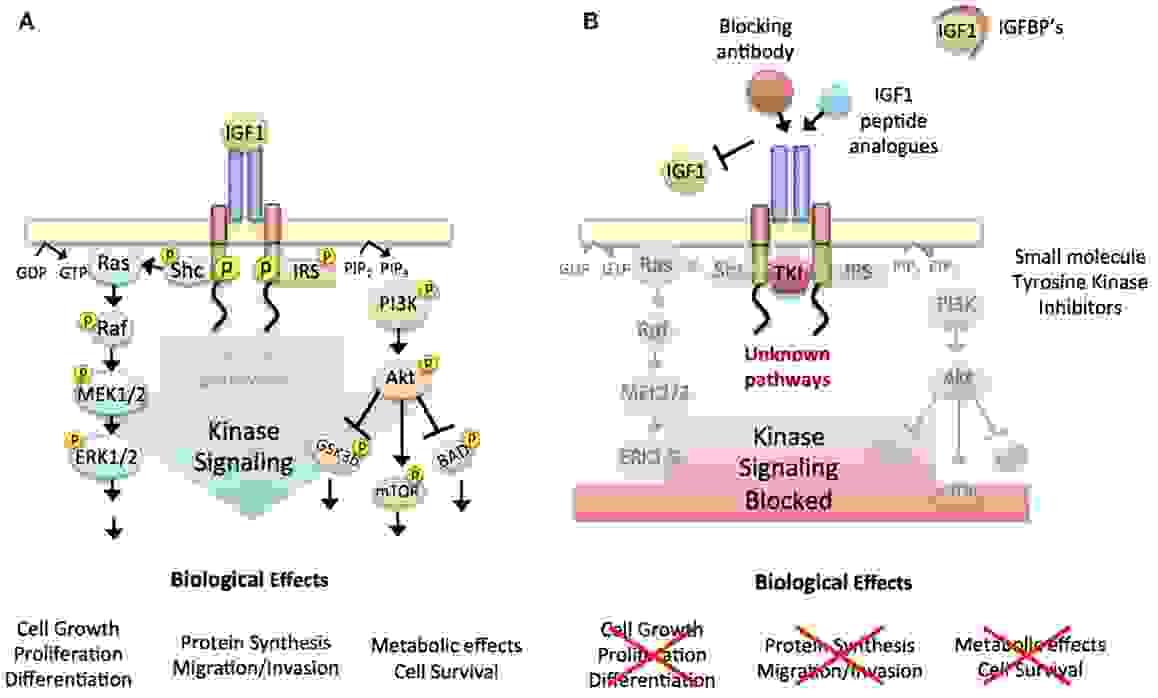

Thyroid Eye Disease (TED) is indeed a complex inflammatory disorder. It involves an autoimmune process where the body's immune system mistakenly targets tissues around the eyes. Research has shown that certain receptors, like the TSH receptor (TSHR) and the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), are overexpressed on orbital fibroblasts in people with TED. Activation of these receptors leads to inflammation, tissue expansion, and changes such as swelling and bulging of the eyes.

This complex interaction of immune cells, antibodies, and receptors drives the characteristic symptoms of TED and makes its management challenging but also an exciting area for ongoing research and therapeutic advances.

FAQs

Add a subtitle here

What is the FAQ section?

What is Strikingly?

How do I create a website?

What Happens in My Eyes?

Let us understand our immune system first

Orbital fibroblasts

Human orbital fibroblasts are specialized cells found in the connective tissue of the orbit. They help maintain the structural integrity of the orbit, produce extracellular matrix components, and contribute to tissue repair and remodeling. They are also involved in various physiological and pathological processes, including inflammation and fibrosis.

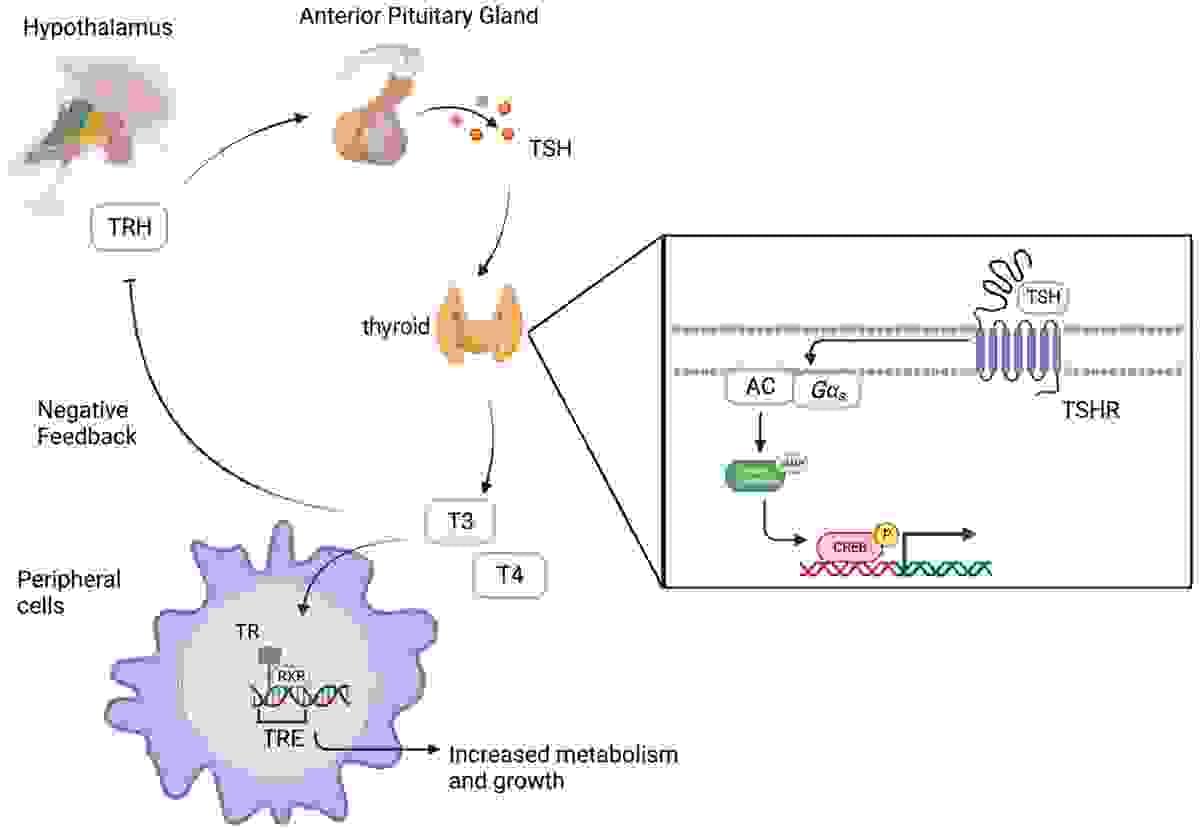

TSHR

The thyrotropin receptor (or TSH receptor) is a receptor (and associated protein) that responds to thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH, also known as "thyrotropin") and stimulates the production of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). The TSH receptor is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily of integral membrane proteins and is coupled to the Gs protein.

Autoantibodies

Autoantibodies are a malfunctioning type of antibody.

Antibodies are proteins your immune system makes to identify and destroy invaders like germs, allergens or toxins in your blood. When your immune system detects a new unwanted substance in your body, it makes antibodies customized to find and destroy that invader.

Autoantibodies harm your body instead of keeping it healthy. They mistakenly target healthy tissue, instead of protecting you from substances that can make you sick. This damage can eventually cause many types of autoimmune diseases.

Thyroid-stimulating autoantibodies

Thyroid antibodies develop when a person’s immune system mistakenly attacks the thyroid cells and tissues. This leads to inflammation, tissue damage or disrupted thyroid function. These antibodies cause autoimmune thyroid disorders, such as Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

If the initial thyroid test results show signs of a thyroid problem, and if there is a suspicion of autoimmune thyroid disease, one or more thyroid antibody tests may be ordered. Antibody tests are used to confirm the diagnosis of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Some people will test positive for more than one type of thyroid antibody.

In people with subclinical thyroid disease, the presence of antibodies can indicate the person may go on to develop full-blown thyroid disease in the future, but that treatment is not yet required. Positive antibodies can also be present in people without thyroid disease.

In Graves’ disease, the thyroid stimulating antibodies (TSAb) mimic the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) secreted by the pituitary gland. This causes the thyroid to continue to produce thyroid hormones, despite the pituitary trying to switch off the thyroid by stopping production of TSH. The presence of TRAb suggests a person has Graves’ disease. Approximately 95% of patients with Graves’ disease will have raised TRAb. The severity of Graves’ disease is often reflected in the levels of TRAb present. For example, where the TRAb levels are very high, the patient is less likely to achieve long-term remission following a course of treatment with antithyroid drugs.

It is sometimes possible for antibodies to be negative, but for a scan to confirm a Graves’ disease diagnosis.

IGF-1R

The insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor is a protein found on the surface of human cells. It is a transmembrane receptor that is activated by a hormone called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and by a related hormone called IGF-2. It belongs to the large class of tyrosine kinase receptors. This receptor mediates the effects of IGF-1, which is a polypeptide protein hormone similar in molecular structure to insulin. IGF-1 plays an important role in growth and continues to have anabolic effects in adults – meaning that it can induce hypertrophy of skeletal muscle and other target tissues.

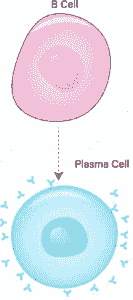

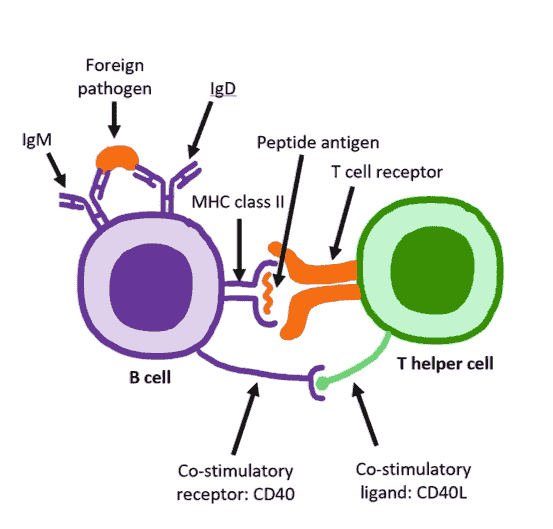

B cells

B cells are a type of white blood cell that makes infection-fighting proteins called antibodies. B cells are an important part of your immune system, your body’s defense against harmful pathogens (viruses, bacteria and parasites) that enter your body and make you sick.

B cells and T cells are a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes. Lymphocytes fight harmful invaders and abnormal cells, like cancer cells. T cells protect you by destroying pathogens and sending signals that help coordinate your immune system’s response to threats. B cells make antibodies in response to antigens (antibody generators). Antigens are markers that allow your immune system to identify substances in your body, including harmful ones like viruses and bacteria.

B cells are also called B lymphocytes.

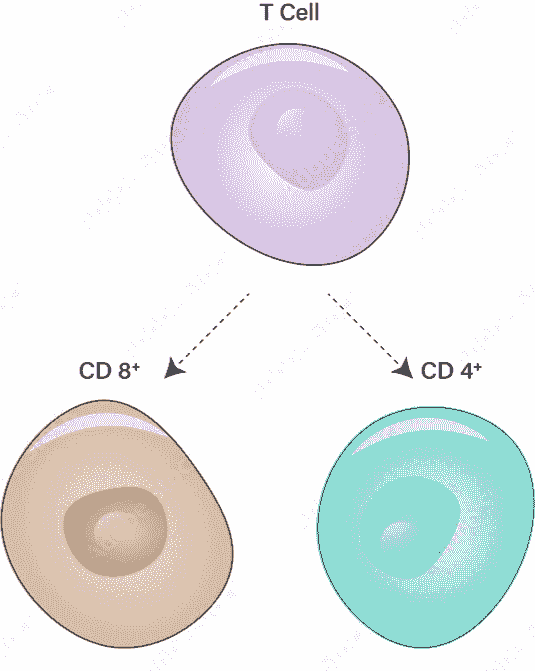

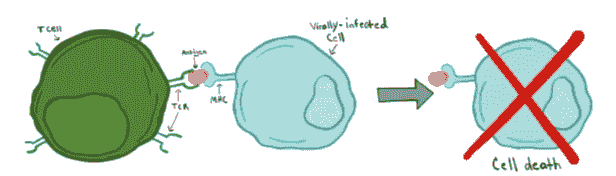

T cells

T cells are a type of white blood cell called lymphocytes. They’re also called T lymphocytes. Lymphocytes play an essential role in your immune system. Your immune system fights infection-causing pathogens (viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites) and harmful cells, like cancer cells.

There are two main types of T cells:

Cytotoxic T cells: Cytotoxic T cells are also called CD8+ cells because they have a CD8 receptor on their membranes. These cells get their name from “cyto,” which means cell, and “toxic,” which means poisonous or harmful. Cytotoxic T cells kill cells infected with viruses and bacteria, and they also destroy tumor cells.

Helper T cells: Helper T cells are also called CD4+ cells because they have a CD4 receptor on their membranes. Unlike cytotoxic T cells, helper T cells don’t kill cells directly. Instead, they send signals that tell other cells in your immune system how to coordinate an attack against invaders. Helper T cells signal cytotoxic T cells, B cells and another type of white blood cell called a macrophage.

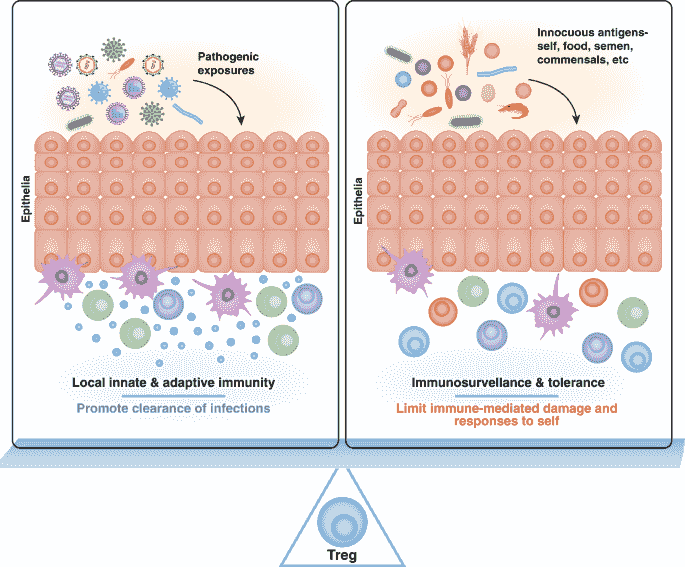

Although they’re not considered one of the main T cell types, regulatory T cells (suppressor cells) play an essential role in your immune system. These cells reduce the activity of other T cells when necessary. They can prevent T cells from attacking your body’s healthy cells.

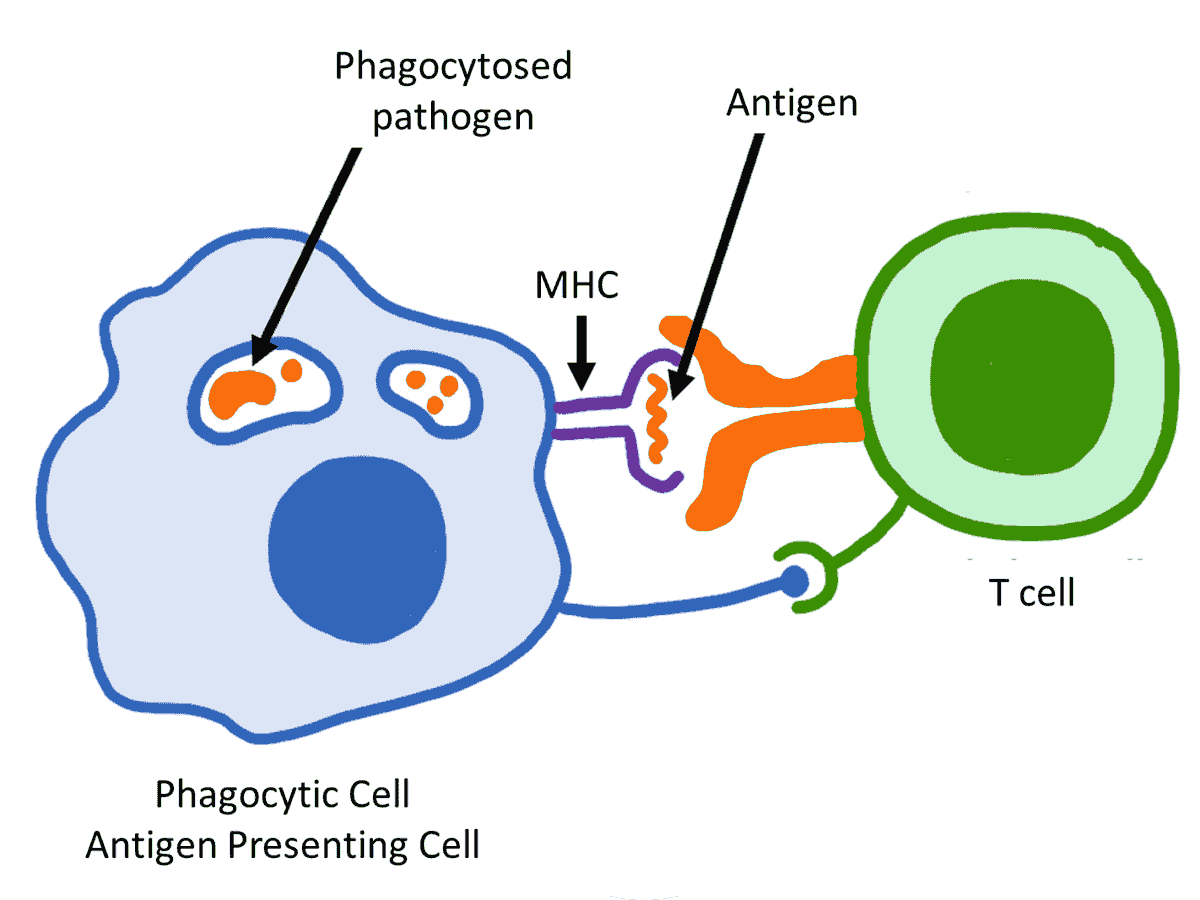

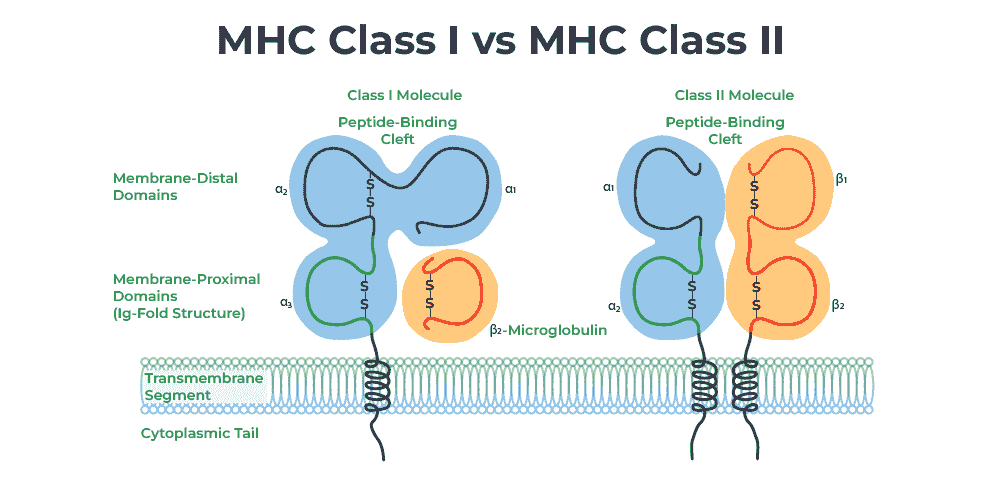

MHC

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are called MHC molecules.

Its name comes from its discovery during the study of transplanted tissue compatibility. Later studies revealed that tissue rejection due to incompatibility is only a facet of the full function of MHC molecules, which is to bind an antigen derived from self-proteins, or from pathogens, and bring the antigen presentation to the cell surface for recognition by the appropriate T-cells. MHC molecules mediate the interactions of leukocytes, also called white blood cells (WBCs), with other leukocytes or with body cells. The MHC determines donor compatibility for organ transplant, as well as one's susceptibility to autoimmune diseases.

MHC II

MHC Class II molecules are a class of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules normally found only on professional antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells, macrophages, some endothelial cells, thymic epithelial cells, and B cells. These cells are important in initiating immune responses.

MHC-II-expressing cells acquire antigen by distinct cellular processes that allow professional APCs to sample their external environment. Classically, extracellular proteins were thought to predominate as antigenic sources in MHC-II presentation, but many studies have demonstrated that the MHC-II peptidome largely consists of peptides derived from endogenous – rather than exogenous – source proteins.

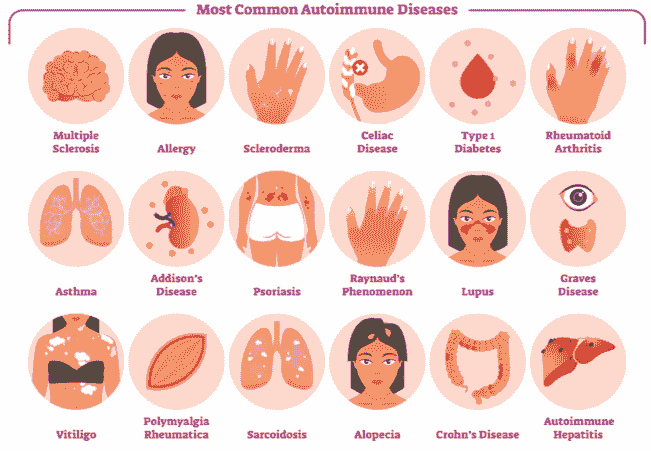

Autoimmune diseases

Autoimmune diseases are health conditions that happen when your immune system attacks your body instead of defending it. Healthcare providers sometimes call them autoimmune disorders.

Usually, your immune system is like your body’s built-in security system. It automatically detects substances that shouldn’t be in your body (like viruses, bacteria or toxins) and sends out white blood cells to eliminate them before they can damage your body or make your sick.

If you have an autoimmune disease, your immune system is more active than it should be. Because there aren’t invaders to attack, your immune system turns on your body and damages healthy tissue.

Autoimmune diseases are chronic conditions. This means if you have an autoimmune disease, you’ll probably have to manage it and the symptoms it causes for the rest of your life.

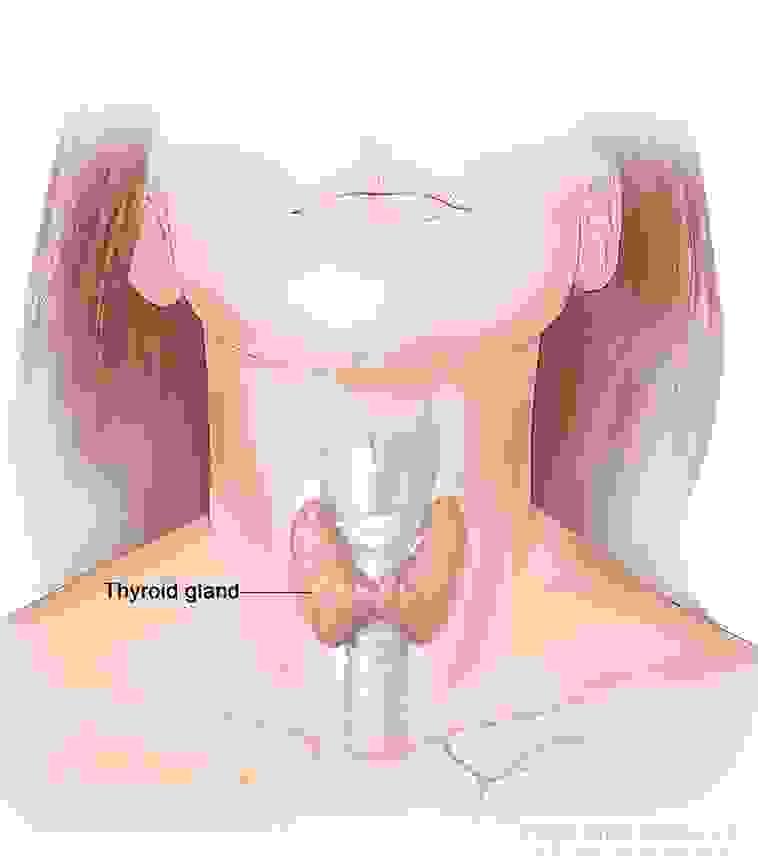

Graves Disease

Graves’ disease is a lifelong (chronic) autoimmune disease that causes your thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. It happens because your body makes antibodies to your thyroid gland.

It’s one of the most common causes of hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid), especially if you have a family history of thyroid problems. Graves’ disease mainly affects your thyroid. But it can also affect your eyes and skin.

Graves’ disease speeds up your metabolism. This can affect several aspects of your health. You may not feel like yourself or even feel out of control of your body. It’s important to get medical treatment if you develop signs of this condition.

Graves’ disease (GD) is an autoantibody-mediated autoimmune disease that is characterized clinically by hyperthyroidism and pathologically by infiltration of thyroid by T and B cells reactive to the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), thyroid peroxidase (TPO), and thyroglobulin (Tg) in most patients. GD is caused by direct stimulation of thyroid epithelial cells by TSHR stimulating antibodies (TSAb), triggering signaling cascades within thyrocytes that lead to over-production and secretion of thyroid hormones resulting in clinical hyperthyroidism .

The A subunit of the extracellular domain of TSHR is the major autoantigen in GD, mediating the T- and B-cell immune responses that cause GD. The sequence of events leading to GD start when pathogenic TSHR peptides are presented by HLA class II on antigen presenting cells to CD4+ T-cells. CD4+ T-cells then recognize the HLA class II-TSHR peptide complex and initiate immune responses, including signals for B-cell proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells, which produce and secrete anti-TSHR stimulating antibodies.

Thyroid eye disease (TED)

Graves’ disease (GD) is a common organ-specific autoimmune disease with an annual incidence of 20 to 50 cases per 100,000 persons. The primary symptoms are hyperthyroidism and goiter, with almost a half of GD patients reporting symptoms of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) is a major thyroid self-antigen, and autoantibodies against TSHR are widely believed to be the cause of hyperthyroidism. Autoantibodies that bind to specific epitopes on the TSHR mimic thyroid-stimulating hormone and induce the secretion of excessive amounts of thyroid hormone from thyroid cells.

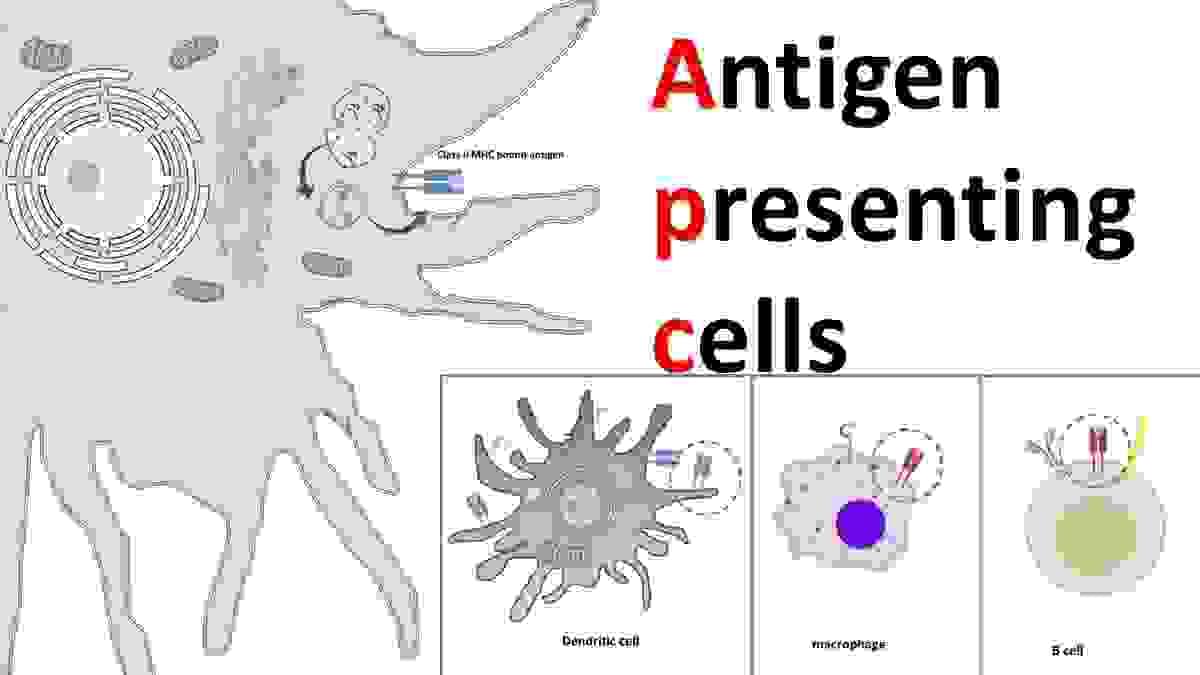

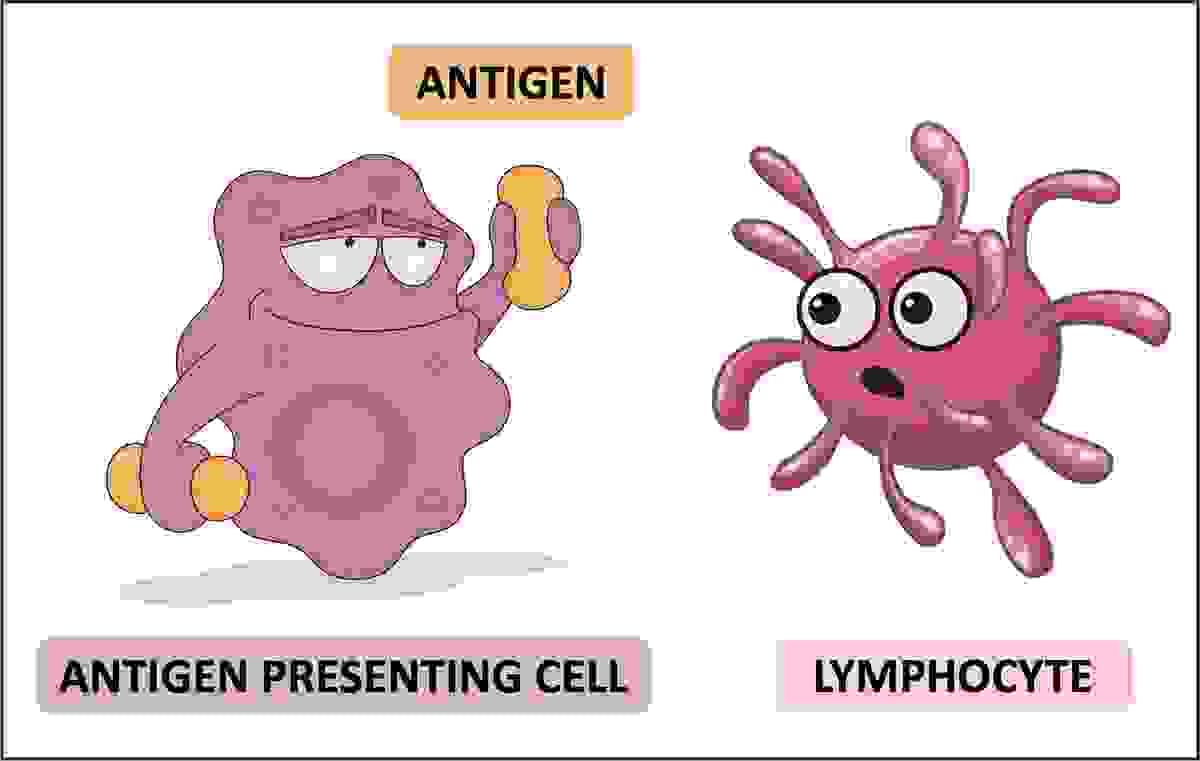

Antigen presenting cell (APC)

An antigen-presenting cell (APC) or accessory cell is a cell that displays an antigen bound by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on its surface; this process is known as antigen presentation. T cells may recognize these complexes using their T cell receptors (TCRs). APCs process antigens and present them to T cells.

Almost all cell types can present antigens in some way. They are found in a variety of tissue types. Dedicated antigen-presenting cells, including macrophages, B cells and dendritic cells, present foreign antigens to helper T cells, while virus-infected cells (or cancer cells) can present antigens originating inside the cell to cytotoxic T cells. In addition to the MHC family of proteins, antigen presentation relies on other specialized signaling molecules on the surfaces of both APCs and T cells.

CD4 T cells

Human CD4+ T cells are critical regulators of the immune system, as drastically demonstrated by HIV-infected individuals that develop susceptibility to opportunistic infections and cancer when virus-dependent depletion reduces CD4+ T cell counts below critical thresholds. CD4+ T cells are very heterogeneous in human adults, because they have been generated in response to a high number of different pathogens and belong to a progressively increasing number of different subsets with specialized functions. Helper T cell subsets are defined by the production of cytokines and/or the expression of characteristic lineage-defining transcription factors. Five principal subsets or lineages of CD4+ T cells have been identified so far: T helper (Th)1, Th2, and Th17 cells that target specific classes of pathogens, regulatory T cells that are required to maintain self-tolerance and follicular helper T cells (TFH) that provide help to B cells for antibody production.

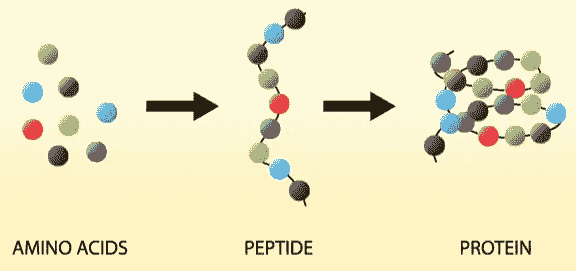

Peptide

Peptides are chains of amino acids (at least two). The acid monomers are connected through peptide linkages and are amongst the most effective known bioactive substances. Examples of such biologically active peptides are hormones, neurotransmitters, or growth factors. The biggest peptide includes up to 100 amino acids. More than 7’000 naturally occurring peptides are known. Longer peptides with three-dimensional shape are called proteins. Peptide synthesis is a chemical process, in contrast to biological substances like antibodies.

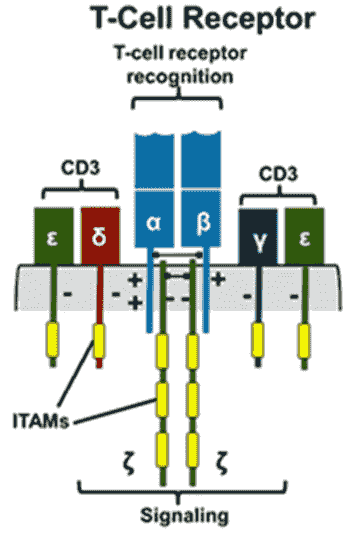

T cell receptor (TCR)

T cell receptors (TCRs) are specific receptors on the surface of T cells that can recognize and bind protein antigens, and are characteristic markers of all T cells. TCR specifically recognizes and binds to specific antigen peptides presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on the surface of antigen presenting cells (APC) to form TCR-antigen peptide-MHC complex (TCR-pMHC complex) , initiate the first transduction signal, thereby inducing the activation of T cells and exerting adaptive immune effector function.

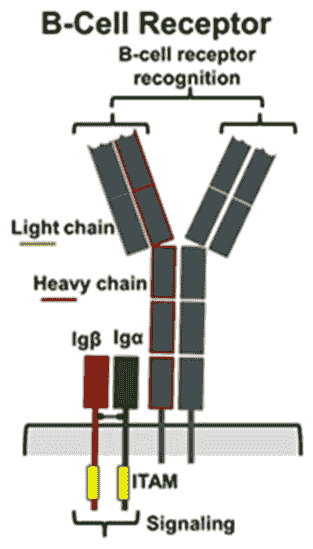

B cell receptor (BCR)

B cell receptor (BCR), also known as B cell antigen receptor, is usually a heterodimeric complex composed of an antigen-binding subunit (membrane surface immunoglobulin, mIg) and a signaling unit. The antigen-binding subunit is a tetramer composed of two heavy chains (H) and two light chains (L) (κ or λ chains), of which the H chain consists of four parts of gene fragments, including 65-100 types of variable regions (VH), 2 types of variable regions (DH), 6 types of binding regions (JH) and constant region (CH); L chain is composed of Three parts of gene fragments, involving variable region (VH), binding region (JH) and constant region (CH) composition. The signaling unit is a heterodimeric protein in which Ig-alpha (Igα, CD79A) and Ig-beta (Igβ, CD79B) are linked by disulfide bonds. The cytoplasmic domain of Ig-alpha is longer and contains 61 amino acids; the cytoplasmic domain of Ig-beta contains 48 amino acids.

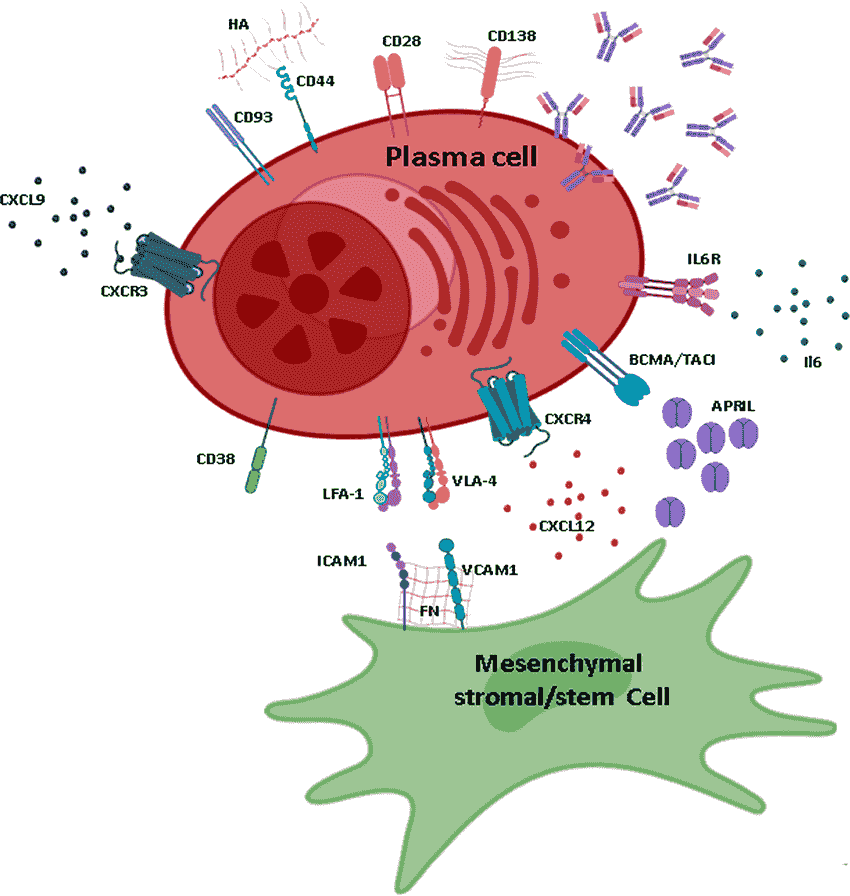

Plasma cell

Also known as plasma B cells, plasma cells are terminally differentiated B lymphocytes. While they originate from activated B cells in the spleen and lymph nodes (secondary lymphoid organs) etc., some plasma cells migrate to the bone marrow where they may persist for an extended period of time.

Here, it's suggested that they interact with the stromal cells that surround the sinusoidal endothelial cells which facilitates the production and release of antibodies into the blood stream.

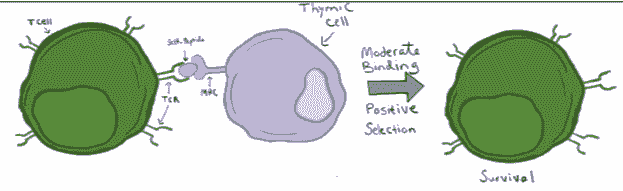

T cell thymic development

T-cells originate from stem cells in the bone marrow and develop in the thymus, a small lymphoid organ located between the lungs. Once in the thymus, immature T cells progress through multiple developmental stages on their road to differentiation into mature T cells capable of recognizing antigens and protecting our bodies from infection. During this period of development, T cells undergo somatic recombination to generate individual T cell clones expressing unique TCRs. These TCRs are key molecules in the identity of each T cell, as they each have the ability to bind and recognize different antigens. In general, this antigen recognition process occurs when the TCR binds to antigen being presented by other cells on MHC proteins (MHC class I in the case of CD8+ T cells, MHC class II in the case of CD4+ T cells). For example, if one of your cells were to be infected by a virus, this infected cell could present viral antigens on its surface via MHC class I molecules, and this antigen-MHC complex would act as a danger signal to the surrounding immune cells. A T cell with a compatible TCR could then bind to the antigen-MHC complex on the infected cell and kill it, thereby preventing the spread of the virus. Given the important role of the TCR in facilitating antigen recognition and cellular killing, it is vitally important that the TCRs produced by somatic recombination 1) are capable of binding MHC complexes and 2) will not recognize our own cells, which also express MHC proteins bound to normal, self-peptides. T cells, then, must walk a very fine line between recognition of that which is foreign and harmful, and that which is self and safe.

Positive Selection

To address the necessity that T cells be capable of binding MHC complexes, T cells undergo positive selection. In this process, cells in the thymus present short pieces of proteins, called peptides, on their own MHC class I and class II molecules, allowing immature T cells to bind. If TCRs are incapable of binding, the T cell will undergo a type of cell death celled apoptosis. If, however, a T cell’s TCR successfully binds to the MHC complexes on the thymic cells, the T cell receives survival signals and is thus positively selected. Further, this positive selection process also determines if a T cell will become a CD8+ T cell or a CD4+ T cell. Specifically, if a TCR complex binds strongly to MHC class II, the complex will send intracellular signals to induce the expression of a protein called ThPOK. This protein reduces the expression of another key protein, called Runx3, responsible for driving CD8 expression. Because low Runx3 causes low CD8, these ThPOK+, Runx3- cells become CD4+. If, however, a developing T cell does not bind strongly to MHC class II, ThPOK levels will be low and thus Runx3 levels will be high, pushing the T cell to differentiate into a CD8+ cell. In sum, the process of positive selection leads to the survival of mature CD8+ and CD4+ T cells capable of recognizing MHC complexes.

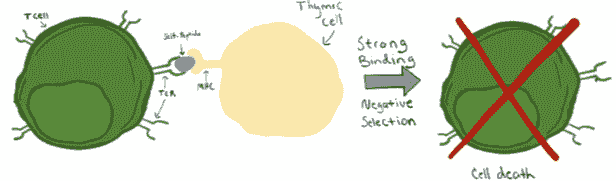

Negative Selection

While the ability of T cells to recognizes antigen-MHC complex is vital for their ability to fight pathogens and other foreign cells, it is equally important that these T cells do not recognize and attack our own cells. This is where negative selection comes into play. As described above, developing T cells in the thymus are presented with peptides bound to MHC molecules, to which they may be able to bind. Importantly, while a moderate degree of binding leads to survival and positive selection, TCRs that bind too strongly to these MHC complexes are destined for the opposite fate (Figure 1, bottom). It is thought that, when TCRs bind too strongly to the MHC complexes in the thymus, the intracellular signaling is so strong that it actually leads to cell death, thereby eradicating immature T cell that have a high likelihood of being self-reactive and attacking our own cells.

One of the most intriguing aspects of negative selection is that it primarily occurs in the thymus, which means that T cells rely solely on the cells in the thymus to present self-peptides on MHC molecules. Because of this, it is tempting to think that negative selection will only delete T cells who show reactivity to thymic self-peptides… but what about peptide-MHC complexes specific to the stomach or the skin or the lungs? Would the T cells that survive negative selection leave the thymus only to kill cells of our other organs? Clearly, this is not the case, and the reason is attributed to a protein called autoimmune regulator, or AIRE. The role of AIRE in the thymus is to induce the expression of many proteins that are not typically expressed in thymic cells, such as proteins characteristic of the lungs. In this way, developing T cells are exposed to many peptide-MHC complexes, not just those normally expressed by thymic cells, thereby preventing autoimmunity once T cells leave the thymus.

Immune tolerance

Immune tolerance, also known as immunological tolerance or immunotolerance, refers to the immune system's state of unresponsiveness to substances or tissues that would otherwise trigger an immune response. It arises from prior exposure to a specific antigen and contrasts the immune system's conventional role in eliminating foreign antigens. Depending on the site of induction, tolerance is categorized as either central tolerance, occurring in the thymus and bone marrow, or peripheral tolerance, taking place in other tissues and lymph nodes. Although the mechanisms establishing central and peripheral tolerance differ, their outcomes are analogous, ensuring immune system modulation.

Immune tolerance is important for normal physiology and homeostasis. Central tolerance is crucial for enabling the immune system to differentiate between self and non-self antigens, thereby preventing autoimmunity. Peripheral tolerance plays a significant role in preventing excessive immune reactions to environmental agents, including allergens and gut microbiota. Deficiencies in either central or peripheral tolerance mechanisms can lead to autoimmune diseases, with conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS-1), and immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome (IPEX) as examples. Furthermore, disruptions in immune tolerance are implicated in the development of asthma, atopy, and inflammatory bowel disease.

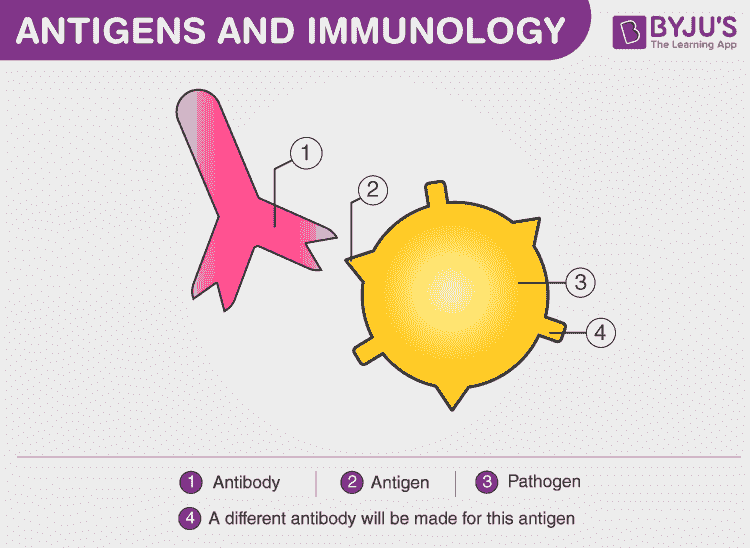

Antigen

Antigens are large molecules of proteins, present on the surface of the pathogen- such as bacteria, fungi viruses, and other foreign particles. When these harmful agents enter the body, it induces an immune response in the body for the production of antibodies.

The immune system has the capacity to distinguish between body cells (‘self’) and foreign materials (‘non-self’)

It will react to the presence of foreign materials with an immune response that eliminates the intruding material from the body

All nucleated cells of the body possess unique and distinctive surface molecules that identify it as self.

These self markers are called major histocompatibility complex molecules (MHC class I) and function as identification tags.

The immune system will not normally react to cells bearing these genetically determined markers (self-tolerance)

Any substance that is recognised as foreign and is capable of triggering an immune response is called an antigen (non self)

Antigens are recognised by lymphocytes which bind to and detect the characteristic shape of an exposed portion (epitope)

Lymphocytes trigger antibody production (adaptive immunity) which specifically bind to epitopes via complementary paratopes

Antigenic determinants include:

- Surface markers present on foreign bodies in the blood and tissue – inluding bacterial, fungal, viral and parasitic markers

- The self markers of cells from a different organism (this is why transplantation often results in graft rejection)

- Even proteins from food may be rejected unless they are first broken down into component parts by the digestive system

Properties of Antigens

- The antigen should be a foreign substance to induce an immune response.

- The antigens have a molecular mass of 14,000 to 6,00,000 Da.

- They are mainly proteins and polysaccharides.

- The more chemically complex they are, the more immunogenic they will be.

- Antigens are species-specific.

- The age influences the immunogenicity. Very young and very old people exhibit very low immunogenicity.

Types of Antigens

Exogenous Antigens

Exogenous antigens are the external antigens that enter the body from outside, e.g. inhalation, injection, etc. These include food allergen, pollen, aerosols, etc. and are the most common type of antigens.

Endogenous Antigens

Endogenous antigens are generated inside the body due to viral or bacterial infections or cellular metabolism.

Autoantigens

Autoantigens are the ‘self’ proteins or nucleic acids that due to some genetic or environmental alterations get attacked by their own immune system causing autoimmune diseases.

Tumour Antigens

It is an antigenic substance present on the surface of tumour cells that induces an immune response in the host, e.g. MHC-I and MHC-II. Many tumours develop a mechanism to evade the immune system of the body.

Native Antigens

An antigen that is not yet processed by an antigen-presenting cell is known as native antigens.

WP1302

Wp1302 can directly bind to MHC class IIextracellularly, inhibiting TSHR-specific autoimmune cells and blocking the

production of TSHR autoantibodies, thereby offering a cue opportunity for the

Graves' disease treatment.WP1302 (ATX-GD-59) consists of twopeptides, S-001 and S-002, derived from key epitopes within the human TSHR,

targeting the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II binding site.

WP1302 has high solubility and does not induce cellular endocytosis or

inflammation. WP1302 mediates the interaction between inactive/immature immune

cells (those lacking co-stimulatory molecules) via MHC II, inducing TSHR

specific immune tolerance. WP1302 will suppress the TSHR-specific T cells and B

cells, reduce the production of stimulating autoantibodies against TSHR.WP1302

WP1302 comprises two soluble syntheticlinear peptides, S-001 and S-002, and is presented as a lyophilized powder for

reconstitution as a solution for subcutaneous injection.The TSHR ECD is of primary importance forthe high affinity binding for TSH and TSAb, and also the most important region

for identification of potential apitopes. Therefore, we have focused on the

TSHR ECD. HLA-DRB1*0301-transgenic (HLA-DR3tg) and HLA-DRB1*0401-transgenic

(HLA-DR4tg) mice have been identified as the preclinical animal model for

studying mechanism of action and pharmacological effects of WP1302.S-001 and S-002 were identified as thepreferred epitopes using our proprietary technology platform through a series

of in vitro and in vivo studies. First, the antigen TSHR was subdivided into

overlapping 30-mers and screened to determine the immunogenic regions within

the TSHR ECD (aa20-418), by testing their capacity to elicit an immune response

in HLA-DR3tg and HLA-DR4tg mice: After immunization of HLA-DR3tg and HLA-DR4tg

mice with TSHR, the overlapping peptides were used to screen the T cell responses

in an in vitro T cell proliferation assay. Several regions were found to be

immunogenic. To further investigate the T cell specificity of the peptides, a

collection of T cell hybridomas was produced. The longer peptide regions were

shortened using 15 amino acid long peptides, and a short list of core peptide

sequences was selected through the results of T-cell hybridoma analysis. The

short list of peptides identified was further tested to determine their ability

to bind to the HLA-DR molecules in an in vitro assay. In parallel with the

HLA-DR3tg and HLA-DR4tg mice system and in vitro activities, the TSHR ECD was

analyzed to confirm that Graves’ Disease patients’ PBMCs recognize the two peptides.Adequate solubility is one of keycharacteristics of the immunogenicity of a peptide. Therefore, peptide

development candidates need to be soluble in aqueous solutions to be

efficacious in inducing tolerance.The native sequence of S-001 is insolublein aqueous solution and therefore has been modified by replacing the N-terminal

isoleucine with a lysine residue and adding three charged lysine amino acid

moieties in the N and C-terminal end to meet the solubility criteria. During

the process of modification, the Apitope functionality was monitored in a

series of assays to secure biological function. The modified peptide sequence

S-001 has been analyzed for homology with other protein sequences in humans and

other species (using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool – BLAST) but no significant match beside identity to TSHR wasobserved.Peptide S-002 fulfilled the Sponsor’s solubility criteria without the need for modification, andtherefore is included as the native sequence in T-cell tolerance induction

study by WP1302 in HLA-DR transgenic mice.There are a number of advantages that theplatform offers over other less specific approaches to induce tolerance (e.g.,

anti-CD3 antibodies). These include:1. Thechosen epitopes have favorable properties for long-term treatment, including

low toxicity, rapid clearance, and a high specificity.2. Insteadof using full-length autoantigens that risk hypersensitivity reactions, this

method employs short peptides based on T cell epitopes, reducing the risk of

severe allergic responses.3. Thesepeptide epitopes are soluble, preventing the formation of aggregates that could

trigger inflammatory responses.4. Theplatform's main safety advantage is its specificity: targeting specific

antigens rather than broadly suppressing the immune system. This has been

validated in both pre-clinical studies and clinical trials, including trials

with ATX-MS-1467 and other peptides (Table 1).Table 1 Summary of the clinicalstudies undertaken using therapeutic peptides that act via MHC Class II protein

Condition

Peptide

Reference

Graves’ Hyperthyroidism

ATX-GD-59

Pearce et al., 2019

Multiple Sclerosis

Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone)

Copaxone SmPC, 2015

Multiple Sclerosis

ATX-MS-1467

Streeter et al., 2015

Chataway et al., 2018

Type 1 Diabetes (TI.D.)

Proinsulin derived peptide C19-A3

Ali et al., 2017

Rheumatoid Arthritis

dnaJP1 derived from bacterial Heat shock protein (HSP)

Prakken et al., 2004

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Lupuzor

Zimmer et al., 2013

Coeliac Disease

Three immunodominant epitopes for gluten-specific

CD4-positive T cells (NPL001,

NPL002, and NPL003)

Goel et al., 2017

Bee Venom Allergy

T cell epitope peptides of the phospholipase A2 (PLA)

Müller et al.,1998

WP1302

Abstract

Thyroid eye disease (TED) remains challenging for clinicians to evaluate and manage. Novel therapies have recently emerged, and their specific roles are still being determined. Most patients with TED develop eye manifestations while being treated for hyperthyroidism and under the care of endocrinologists. Endocrinologists, therefore, have a key role in diagnosis, initial management, and selection of patients who require referral to specialist care. Given that the need for guidance to endocrinologists charged with meeting the needs of patients with TED transcends national borders, and to maximize an international exchange of knowledge and practices, the American Thyroid Association and European Thyroid Association joined forces to produce this consensus statement.

Keywords: thyroid eye disease, consensus statement, American Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association

1. Summary of Key Points 1440

2. Introduction 1441

2.1 Methods 1442

3. Background 1442

3.1. Epidemiology 1442

3.2. Natural history 1443

3.3. Pathogenesis 1443

3.4. Risks for TED development and opportunities for prevention 1443

3.5. Early diagnosis and referral for TED specialty care 1443

3.6. Role of endocrinologists and ophthalmologists in the care of patients with TED 1444

4. Patient Assessment 1445

4.1. Assessing disease activity and severity 1445

4.2. Assessment of quality of life 1446

4.3. Formal ophthalmology evaluation 1446

4.4. Imaging 1448

5. Overall Approach to Therapy 1449

5.1. Local and lifestyle measures 1449

5.2. Overview of systemic medical and surgical treatments for TED 1449

5.3. Setting for TED care 1449

5.4. Referral to ophthalmology 1449

6. Therapy for Mild TED 1451

6.1. Medical therapy for mild TED 1451

6.2. Surgery for minimal changes in proptosis and lid retraction 1451

7. Management of Moderate-to-Severe TED 1451

7.1. Medical therapies 1451

7.1.1. Glucocorticoids 1453

7.1.2. Therapies for patients with moderate-to-severe TED unresponsive or intolerant to intravenous glucocorticoids 1456

7.1.3. Teprotumumab 1457

7.1.4. Rituximab 1458

7.1.5. Mycophenolate 1459

7.1.6. Tocilizumab 1460

7.1.7. Other agents 1461

7.1.7.1. Other agents tested in TED patients and clinically available 1461

7.1.7.2. Other agents under investigation in TED patients but not clinically available 1461

7.1.7.3. Other agents tested in GD patients with potential benefit in TED but not clinically available 1461

7.2. Radiotherapy for moderate-to-severe TED 1461

7.3. Surgical intervention for inactive moderate-to-severe TED 1462

7.3.1. Surgical intervention overview 1462

7.3.2. Orbital decompression 1462

7.3.3. Strabismus procedures 1463

7.3.4. Eyelid procedures 1463

8. Therapy for Sight-Threatening TED 1463

8.1. Intravenous glucocorticoids 1463

8.2. Radiotherapy in dysthyroid optic neuropathy 1464

8.3. Orbital decompression for dysthyroid optic neuropathy 1464

9. Overview of the Management of TED 1465

10. Research Gaps in the Management of TED 1465

1. SUMMARY OF KEY POINTS

1.1. Diagnosis and assessment

Key Point 3.1: Early diagnosis of TED and simple measures to prevent TED development or progression should be pursued.

Key Point 3.2: Endocrinologists managing patients with Graves' disease should identify referral pathways that ensure patient access to TED specialty care.

Key Point 3.3: Ophthalmologists are key to the management of TED and should always be involved in the care of patients with moderate-to-severe and sight-threatening TED.

Key Point 4.1.1: Endocrinologists should be familiar with basic elements of a TED examination enabling assessment of both activity and severity.

Key Point 4.1.2: Assessment of patients with TED should include activity, severity (with particular attention to impaired ocular motility and visual loss), trend across time, and impact on daily living.

Key Point 4.2.1: The physical and psychosocial impact of TED should be assessed for each patient, as it informs treatment decisions. When formal quantification of quality of life (QOL) is deemed appropriate, Graves' orbitopathy-quality of life (GO-QOL) is the preferred instrument.

Key Point 4.4.1: Orbital imaging using contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred for atypical or severe cases of TED to help determine activity and to exclude other etiologies that could be confused with TED.

Key Point 4.4.2: Noncontrast CT is the preferred modality in patients with TED who are being considered for surgery.

1.2. Initial care and referral for specialty care

Key Point 5.1.1: Local ocular measures and lifestyle intervention should be offered to all patients with TED. Lubricants and nocturnal eye masks may be used to prevent or treat corneal exposure. Ocular occlusion and prisms may be offered to relieve diplopia. The importance of smoking reduction or cessation should be explained, and smokers offered support for this goal.

Key Point 5.3.1: Input from both endocrinologists and ophthalmologists with TED expertise is recommended for optimal management in patients with moderate-to-severe and sight-threatening TED.

Key Point 5.4.1: An ophthalmologist should be consulted when the diagnosis of TED is uncertain, in cases of moderate-to-severe TED, and when surgical intervention needs to be considered. Urgent referral is required when sight-threatening TED is suspected or confirmed.

Key Point 6.1.1: A single course of selenium selenite 100 μg twice daily for 6 months may be considered for patients with mild, active TED, particularly in regions of selenium insufficiency.

Key Point 6.2.1: The clinician should regularly assess the psychosocial impact of concerns about appearance.

1.3. Therapy of moderate–severe TED

Key Point 7.1.1: Infusion therapies for TED should be administered in a facility with appropriate monitoring under the supervision of experienced staff. Awareness and surveillance for adverse side effects are recommended throughout the treatment period.

Key Point 7.1.2: Clinicians should balance the demonstrated efficacy of recently introduced therapies against the absence of experience on sustained long-term efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness.

Key Point 7.1.1.1: Intravenous glucocorticoid (IVGC) therapy is a preferred treatment for active moderate-to-severe TED when disease activity is the prominent feature in the absence of either significant proptosis (see Section 2.1. for definition) or diplopia.

Key Point 7.1.1.2: Standard dosing with IVGC consists of intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) at cumulative doses of 4.5 g over ∼3 months (0.5 g weekly × 6 weeks followed by 0.25 g weekly for an additional 6 weeks).

Key Point 7.1.1.3: Poor response to IVMP at 6 weeks should prompt consideration for treatment withdrawal and evaluation of other therapies. Clinicians should be alert for worsening diplopia or onset of dysthyroid optic neuropathy (DON) that have occurred even while on IVMP therapy.

Key Point 7.1.1.4: A cumulative dose of IVMP >8.0 g should be avoided.

Key Point 7.1.2.1: Rituximab (RTX) and tocilizumab (TCZ) may be considered for TED inactivation in glucocorticoid (GC)-resistant patients with active moderate-to-severe TED. Teprotumumab (TEP) has not been evaluated in this setting.

Key Point 7.1.3.1 TEP is a preferred therapy, if available, in patients with active moderate-to-severe TED with significant proptosis (see Section 2.1. for definition) and/or diplopia.

Key Point 7.1.4.1: Evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is limited and divergent but suggests efficacy of RTX for inactivation of TED and prevention of relapses at >1 year, particularly in patients with TED of <9 months' duration.

Key Point 7.1.4.2: RTX therapy is acceptable in patients with active moderate-to-severe TED and prominent soft tissue involvement.

Key Point 7.1.6.1: TCZ is an acceptable treatment for TED inactivation in GC-resistant patients with active moderate-to-severe disease.

Key Point 7.2.1: Radiotherapy (RT) is a preferred treatment in patients with active moderate-to-severe TED whose principal feature is progressive diplopia.

Key Point 7.2.2: RT should be used cautiously in diabetic patients to avoid possible retinopathy. It is relatively contraindicated for those younger than 35 years of age to avoid a theoretical lifetime risk of tumors developing in the radiation field.

Key Point 7.3.1.1: Surgery for moderate-to-severe TED should be performed by an orbital surgeon experienced with these procedures and their complications.

Key Point 7.3.1.2: Rehabilitative surgery for moderate-to-severe TED should only be performed when the disease is inactive and euthyroidism has been achieved and maintained.

Key Point 7.3.2.1: The specific surgical approach should be tailored to the indication (DON, proptosis), type of orbitopathy (muscle or fat predominant congestive disease), and desired reduction in proptosis.

Key Point 7.3.3.2: In patients with diplopia and inactive TED, binocular single vision in the primary position of gaze may be restored with strabismus surgery or permanent prisms ground into the spectacle lenses.

Key Point 7.3.4.1: Eyelid retraction and fat prolapse are surgically corrected when TED is inactive and euthyroidism is achieved, and after surgical decompression and strabismus surgery as indicated.

1.4. Therapy of sight-threatening TED

Key Point 8.1.1: Patients with DON require urgent treatment with IVGC therapy, with close monitoring of response and early (after two weeks) consideration for decompression surgery if baseline visual function is not restored and maintained with medical therapy.

Key Point 8.2.1: RT may be considered for preventing or as an adjunct to treating DON.

Key Point 8.3.1: In patients with compressive DON, orbital decompression of the deep medial wall and orbital floor should be considered to restore vision by reducing apical compression on the optic nerve.

2. INTRODUCTION

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is an autoimmune condition closely related to Graves' disease. It is characterized by endomysial interstitial edema, expansion, and proliferation of cells within the fibrofatty compartment, resulting in the clinical manifestations of periorbital edema, lid retraction, proptosis, diplopia, corneal breakdown, and in rare cases optic nerve compression. TED remains challenging for clinicians to evaluate and manage. Novel therapies have recently emerged, and their specific roles are still being determined.

Most patients with TED develop eye disease while being treated for hyperthyroidism under the care of endocrinologists. Endocrinologists, therefore, have a key role in diagnosis, initial management, and selection of patients who require referral to specialist care. Given that the need for guidance to endocrinologists charged with meeting the needs of patients with TED transcends national borders, and to maximize an international exchange of knowledge and practices, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and European Thyroid Association (ETA) joined forces to produce this consensus statement (CS).

The scope was to address clinical assessment, to develop criteria for referral to specialty care and treatment, and to focus on medical and surgical treatment in nonpregnant adults (age ≥18 years) with TED. This CS is primarily aimed at endocrinologists and, in particular, those involved in the management of nonpregnant adult (>18 years) patients with TED. A CS was selected as the forum, rather than a clinical practice guideline, to provide a concise and timely appraisal of a rapidly changing therapeutic arena.

In line with the official policies of the ATA and ETA, this CS is intended as an aid to practicing endocrinologists. It does not establish a standard of care, replace sound clinical judgment, or capture all nuances likely to be present in any particular patient; specific outcomes are not guaranteed. We recommend that treatment decisions be based on independent judgments of health care providers carefully considering each patient's individual circumstances such as comorbidities, functional status, goals of care (established at the outset and revisited frequently), and feasibility considerations, including regional access to specific health care resources. Our recommendations are not intended to supplant patient directives.

A recent survey of ATA and ETA members1 found that 53% reported no access to a multidisciplinary clinic, and the cost of some medical treatments was deemed to be a barrier. The CS has taken this important information into account and has striven to achieve a balance between the limitations imposed by the above constraints and encouraging best practice.

2.1. Methods

Membership in the task force (TF) included physicians with expertise in thyroidology and TED, and adherence to the rules of the ATA and ETA on conflicts of interest (https://www.thyroid.org/wp-content/uploads/members/fin-disclosure-coi-policies-2018.pdf; https://www.eurothyroid.com/files/download/ETA-Rules-for-Guidelines-2016.pdf). Cochairs were nominated by ATA and ETA leadership and invited to suggest up to four additional individuals to represent the ATA and ETA. Potential members were discussed and vetted with ATA and ETA society leadership before the final taskforce was assembled.

A series of twice-monthly virtual meetings of the TF with an average attendance of 88% of members took place between January and November 2021, complemented by additional communications. A literature search of PubMed was initially conducted of English language publications from January 1990 through January 2021 and continuously updated up until the time of publication, using the search terms “thyroid eye disease” or “Graves' orbitopathy” or “Graves' ophthalmopathy” or “thyroid-associated eye disease.” References were imported into EndNote and the final database included 3952 unique references. The scope was discussed, agreed upon, and endorsed by the ATA and ETA. A detailed list of subtopics was constructed with approximate word and reference limits assigned to writing groups based on expertise.

Section drafts were reviewed by the TF. Recommendations were listed as “Key Points,” and discussed and modified until full consensus was reached. Specifically, for topics in which there were differing views among taskforce members, a comprehensive discussion took place, allowing iterative modification of the topic content until there was unanimous consensus. The final drafts were approved by the entire TF. Two patient-led organizations, the Graves' Disease and Thyroid Foundation and the Thyroid Organization of the Netherlands, were invited to review the final draft.

In addition, the CS was posted on the ATA and ETA websites for comments and feedback from members. Feedback was also received from the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery; the European Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery was invited to review the CS, but no feedback was received.

The TF chose the descriptor “TED” because it is commonly used in the literature and is meaningful to specialists, generalists, patients, and the general public, although the TF acknowledges that Graves' orbitopathy is also a widely accepted and frequently used term. Multidisciplinary specialized TED care, described hereunder (see Section 3.5), will be referred to as “TED specialty care.”

Several medical therapies are available for TED. Many have not been compared with placebo or compared with one another in randomized controlled studies. Therefore, the TF has categorized treatments as (1) preferable, (2) acceptable, or (3) may be considered, based on its collective interpretation of the available evidence. A treatment is listed as “preferred” if more than or equal to two RCTs have shown efficacy against standard of care or placebo with concordant results; “acceptable” when there exist more than or equal to two RCTs with discordant results but the discordance is deemed likely the result of differing inclusion criteria, or only a single RCT is available and shows efficacy.

Notably, most included RCTs were not placebo-controlled, but, rather, compared with other existing therapies. A therapy is listed as “may be considered” in the case of therapies for which benefit is not clear. Evidence for efficacy in this category may be the result of more than or equal to two RCTs with discordant results that are not easily explicable, or from single RCTs with small efficacy effects, and from larger well-performed observational studies. In general, therapies in the “may be considered” category are utilized in clinical practice only when both preferable and acceptable therapies are unavailable, contraindicated, or the patient is intolerant and/or refuses.

These definitions leave open the possibility of more than one preferable therapy for a given patient, in which case drug availability, cost, and patient acceptability are paramount in selecting the appropriate therapy for a particular patient. The TF is aware that regional differences currently exist in the availability of individual medical therapies and, therefore, some treatments listed as preferable will not be available in all regions of the world.

For therapies selected to reduce proptosis, the TF elected to use the term “significant proptosis” rather than a numerical threshold (i.e., ≥3 mm above the upper limit for race and sex) as a numerical definition would exclude some patients who might otherwise benefit from therapy. In keeping with the definition of moderate-to-severe TED (Table 1), a degree of proptosis <3 mm above the upper limit for race and sex would be regarded as “significant proptosis” if it impacted sufficiently on daily life and would justify the risks of treatment.

Table 1.

Activity and Severity Definitions for Patients with Thyroid Eye Disease

A. Activity 1. Clinical activity score The 7-item CAS is shown hereunder. Each item scores 1 point if presenta Spontaneous retrobulbar pain Pain on attempted up or lateral gaze Redness of the eyelids Redness of the conjunctiva Swelling of the eyelids Inflammation of the caruncle and/or plica (Fig. 2b) Conjunctival edema, also known as chemosis (Fig. 2c) 2. Active TED A CAS ≥3/7 usually implies active TED. A history or documentation of progression of TED based on subjective or objective worsening of vision, soft tissue inflammation, motility, or proptosis is suggestive of active TED independently of the CASB. Severity 1. Sight-threatening TED Patients with DON and/or corneal breakdown and/or globe subluxation (Fig. 2f) 2. Moderate-to-severe TED Patients without sight-threatening disease whose eye disease has sufficient impact on daily life to justify the risks of medical or surgical intervention. Patients with moderate-to-severe TED usually have any one or more of the following: lid retraction ≥2 mm, moderate or severe soft tissue involvement, proptosis ≥3 mm above normal for race and sex, or diplopia (Gorman score 2–3). 3. Mild TED Patients whose features of TED have only a minor impact on daily life insufficient to justify immunosuppressive or surgical treatment. They usually have only one or more of the following: minor lid retraction (<2 mm), mild soft tissue involvement, proptosis <3 mm above normal for race and sex, transient or no diplopia, and corneal exposure responsive to lubricants.

A 10-item CAS is also sometimes used and includes additional points for increase of at least 2 mm in proptosis, decrease of at least 8° in any duction, and decrease of visual acuity by two lines. A limitation of the 10-item CAS is that it requires an earlier assessment of the mentioned measures, which is usually unavailable on first consultation. See Bartalena et al.19

CAS, clinical activity score; DON, dysthyroid optic neuropathy; TED, thyroid eye disease.

3. BACKGROUND

3.1. Epidemiology

There is a close temporal relationship between the onset of hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease (GD) and TED for patients in whom both disorders occur; in 80% of such cases, both hyperthyroidism and TED develop within 2 years.2 Rarely, TED occurs in euthyroid patients or in those with a history of chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. Notably, TED is almost always seen in conjunction with circulating thyrotropin (TSH) receptor antibodies (TRAbs).3,4

The overall prevalence of TED among patients with GD is up to 40%.5 Recent studies indicate that the clinical phenotype of GD at onset is becoming milder with respect to the prevalence and severity of hyperthyroidism, goiter, and TED.6 Moderate-to-severe and sight-threatening TED now occur in ∼6% and 0.5% of patients with GD, respectively.7 Moreover, TED is a heterogeneous disorder and some clinical variants of the disease (e.g., euthyroid TED) are considered rare.8

3.2. Natural history

The initial description of three phases of TED by Rundle and Wilson remains the widely accepted representation of its natural history.9 An initial active phase is characterized by inflammatory changes, followed by a brief static phase, and lastly by the inactive phase, which patients usually enter 12–18 months after disease onset. Although improvement in signs and symptoms occurs during the latter period, proptosis and extraocular muscle dysfunction frequently do not normalize without intervention and may persist in up to 50% of patients.9

3.3. Pathogenesis

TED develops from an autoimmune-mediated inflammation targeting connective tissue within and around extraocular muscles (EOMs), intraorbital fat, and less frequently lacrimal glands of some patients with GD.2,10 The close link between TED and TRAb supports the hypothesis that the TSH receptor (TSHR) is the primary autoantigen. The insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), with which TSHR forms a functional signaling complex on orbital fibroblasts, seems also to be involved in orbital inflammation, adipogenesis, and tissue remodeling.11

The histopathological changes correlate with the natural history and provide a mechanical basis for understanding the clinical features of TED. Infiltration of orbital tissues by lymphocytes and accumulation of hydrophilic glycosaminoglycans, interstitial edema, and increased adipogenesis are the characteristic findings in the active phase of disease. Increased fibrosis and fat infiltration of affected tissues are observed in the inactive phase.2,10

3.4. Risks for TED development and opportunities for prevention

Nonmodifiable risks for the development and severity of TED include older age, male sex, and genetic factors. The potential role of race in TED remains unclear,7 with anatomic differences in both normal and TED orbits postulated to account for variable presentation by race.12

Modifiable risk factors include cigarette smoking, thyroid dysfunction, and the use of radioactive iodine (RAI). Additional potentially modifiable factors are oxidative stress and elevated serum TRAb levels, the latter affected by choice of therapy for hyperthyroidism.7 Epidemiological studies have recently shown that statin therapy is associated with a decreased risk of developing TED in patients with GD.13–15

The use of steroid prophylaxis in those receiving RAI and normalization of thyroid hormone levels and selenium supplementation in those with mild active disease may alter the natural history of TED7 (Fig. 1). Moreover, based on four independent variables (clinical activity score [CAS], serum TRAb levels, duration of hyperthyroidism, and smoking), a quantitative predictive score for identifying patients with GD least likely to develop TED (negative predictive value of 0.91) has been proposed.16 The low positive predictive value (0.28) of this predictive score limits the utility in predicting future TED.

FIG. 1.

Steps to Reduce Morbidity and Improve Quality of Life in Patients with TED. Measures to reduce morbidity associated with TED and improve patients' QOL. (This figure is used and adapted with permission, courtesy of the British Thyroid Foundation, from the Thyroid Eye Disease Amsterdam Declaration Implementation Group UK (TEAMeD) (https://www.btf-thyroid.org/teamed-page) and Dr. Anna Mitchell. The Thyroid Eye Disease Amsterdam Declaration is further described in references 17, 20). Abs, antibodies; GD, Graves' disease; RAI, radioiodine; TED, thyroid eye disease.

3.5. Early diagnosis and referral for TED specialty care

Adoption of a set of simple measures to promote early diagnosis and prevention of TED is recommended by professional organizations,17–19 following the Amsterdam Declaration.20 It is important that endocrinologists have access to specialized clinical services for patients with TED. Five components are essential for optimal management of patients with TED:

Multidisciplinary decision making based on close communication between experts and patients, utilizing shared decision making.

Coordinated care that encompasses the management of both thyroid and orbital disease.

Skills and expertise for the diagnosis, assessment, and treatment by specialists in TED from endocrinology, ophthalmology, orthoptics (for motility testing and prism fitting) and, as needed, otolaryngology/maxillofacial/plastic surgery, clinical psychology/counseling (with expertise in coping skills related to the impairment of QOL related to TED), nuclear medicine, radiology, and radiation oncology.

Availability of evidence-based treatments.

Safe and timely delivery of treatments.

The format of such a service may be a “Combined Thyroid Eye Clinic,”21 variants of this model in a physical or virtual setting, or a combination of both. The organizational details vary between countries and health care systems and are less important than satisfying the mentioned components. While a combined TED clinic structure can promote quality care in a timely manner,22,23 there is no clear evidence that this model of care is superior to others, and delivery of multidisciplinary care is more important than the structure of the clinic.

3.6. Role of endocrinologists and ophthalmologists in the care of patients with TED

Endocrinologists

manage the thyroid dysfunction,

diagnose TED among their patients with GD,

initiate local and lifestyle measures (Section 5.1),

consider checking selenium level (as indicated), 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, and lipid levels (optional),

refer to ophthalmologists those patients in whom the diagnosis or severity of TED is unclear, and all cases of moderate-to-severe and sight-threatening TED, and

contribute to TED specialty care management decisions including the delivery of systemic therapies, and monitor for adverse events (AEs) of such therapies.

General ophthalmologists:

Diagnose/confirm TED

Provide emergency management of sight-threatening TED after hours

Refer patients with moderate-to-severe or sight-threatening TED to specialty TED care

TED specialty care (Section 3.5)

Diagnose/confirm TED

Medical and surgical management of moderate-to-severe and sight-threatening TED

Ensure optimal management of thyroid disease

Key Point 3.1: Early diagnosis of TED and simple measures to prevent TED development or progression should be pursued.

Key Point 3.2: Endocrinologists managing patients with GD should identify referral pathways that ensure patient access to TED specialty care.

Key Point 3.3: Ophthalmologists are key to the management of TED and should always be involved in the care of patients with moderate-to-severe and sight-threatening TED.

4. PATIENT ASSESSMENT

4.1. Assessing disease activity and severity

A primary objective in the evaluation of TED is to assess factors that inform management and predict outcomes. There is an important distinction in TED between the two interdependent components of inflammatory activity, manifested by pain, redness, and edema, and disease severity, including proptosis, lid malposition, exposure keratopathy (Fig. 2e), impaired ocular motility, and optic neuropathy. The presence of multiple features of inflammation usually signifies active disease. A history of progressive TED further supports the presence of active disease. Definitions of activity and severity are given in Table 1.

FIG. 2.

Composite of selected clinical features in patients with TED. Patient photographs provided with their consent demonstrate (a) lagophthalmos (inability to close eyelid completely); (b) edema and hyperemia of the caruncle (white arrow) and plica (black arrow) (courtesy of P. Perros); (c) chemosis (conjunctival edema) (courtesy of P. Perros); (d) lateral flare due to upper eyelid retraction (courtesy of P. Perros); (e) exposure keratopathy (courtesy of P. Perros); (f) globe subluxation. This is a rare complication in which the eye is displaced anterior to the retracted eyelids. Trapping of the globe may result in painful keratopathy or vision loss. This patient is seen at time of urgent surgery to decompress the orbits and narrow the lid aperture (courtesy of P. Dolman); (g) superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis in eye associated with marked upper lid retraction. This chronic recurring condition is often associated with thyroid disorders and is characterized by enlarged vessels and subepithelial edema involving the superior bulbar conjunctiva and corneal limbus (courtesy of P. Dolman).

When it is unclear whether the disease is active, repeating the assessments after an interval of 4–6 weeks will usually provide the answer, based on a measurable worsening in disease symptoms and signs. The small proportion of patients with TED who subsequently progress to sight-threatening disease can often be identified from the history and examination.24,25 These “high-risk” TED patients are characterized by the features given in Table 2. Such cases merit close follow-up.

Table 2.

Characteristics of High-Risk Thyroid Eye Disease Patients

Background Male sex Age >50 years Tobacco smokerHistory Unstable thyroid function Diabetes mellitus Radioiodine in the past 6 months Progressive symptoms and/or signs of TED Orbital aching DiplopiaExamination Marked soft tissue inflammatory features Lagophthalmos (Fig. 2a) Impaired ocular motility, particularly elevation

The features outlined are associated with an increased probability of developing sight-threatening TED.24

Endocrinologists should be familiar with basic elements of the eye examination for patients with TED as needed to grade severity and activity, according to the worst affected eye. Diagnostic criteria for TED as well as key elements of the eye examination for nonophthalmologists are reviewed in Supplementary Figure S3. A 5-minute patient assessment tool combining subjective and basic objective patient evaluation to diagnose TED and determine a need for ophthalmology referral was found to be efficacious in a pilot trial.26

The most widely used assessment of TED activity is the CAS, adopted by the EUGOGO19 and the ATA clinical practice guidelines on the management of hyperthyroidism.18 A 7-point CAS is currently favored for clinical evaluation that includes pain, erythema, and edema, whereas the 10-point version assesses change over time, using three additional points for worsening proptosis, motility, or visual acuity27 (Table 1). Advantages of CAS include its use of purely clinical parameters and moderate ability to predict response to immunomodulatory therapy.27,28

Examples of CAS elements with patient photographs are provided in open access at (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01349.x). Disadvantages include the binary (yes/no) classification in each category, assignment of equal weight to parameters with divergent clinical importance, and being prone to both false positive (congestive orbitopathy) and false negative predictions (aging and darker skin complexion) of response to treatment.29,30

Assessment of TED severity allows an appraisal of the patient's immediate or future threat to vision, a semiquantitative method for determining change over time, as well as for use in research to facilitate interstudy comparison and meta-analysis. Specific ophthalmic measures including visual acuity, ocular motility and alignment, proptosis, and lid retraction can be accurately documented along with their changes in the clinical assessment of TED severity. A widely used method for broadly categorizing TED severity recommended by EUGOGO19 classifies patients as having mild, moderate-to-severe, and sight-threatening disease (Table 1).

Certain clinical parameters indicate a higher risk for development of sight-threatening TED. Features suggesting a threat to vision include spontaneous orbital aching, diplopia, or restriction of eye movements and lagophthalmos (incomplete lid closure), evolving over a period of weeks or months (Fig. 2a).24 In addition, decreased visual acuity, color vision or visual field, a relative afferent pupillary defect (Marcus-Gunn pupil), and optic disk swelling or pallor are indicative of optic neuropathy. Along with the objective changes of the parameters that comprise severity of TED, its impact on daily living should be noted (see Section 4.2, on assessment of QOL).

A comprehensive assessment system for gauging both activity and severity is known as VISA (standing for vision, inflammation, strabismus, and appearance). The VISA Clinical Recording Form (https://thyroideyedisease.org/clinical-visa-recording-forms/) grades both disease severity and activity using subjective and objective inputs. It organizes the clinical measurements of TED into four severity parameters: V (vision, DON); I (inflammation, congestion); S (strabismus, motility restriction); and A (appearance, exposure).

A summary grade for each severity parameter is recorded at the end of the form so that directed therapy may be chosen based on the parameters involved.30 Activity is determined at the first visit by subjective progression in any VISA symptoms over the previous 2 months, or by documented worsening clinical measurements between visits.

Key Point 4.1.1: Endocrinologists should be familiar with basic elements of a TED examination enabling assessment of both activity and severity.

Key Point 4.1.2: Assessment of patients with TED should include activity, severity (with particular attention to impaired ocular motility and visual loss), trend across time, and impact on daily living.

4.2. Assessment of QOL

TED has major negative effects on QOL.31 Impairment in function may negatively impact daily activities (reading, driving, computer work, and watching television), as well as result in dry eye, photophobia, and retro-orbital pain.31 Changes in appearance may lead to psychosocial disability.32–34 In general, the negative effects on QOL correlate with activity and severity and may persist for years.35 The impact of TED on QOL also depends on the specific cultural and psychosocial circumstances of each individual patient and is an important parameter that influences decisions about treatment. Furthermore, the risk-to-benefit ratio of the proposed therapeutic choices should fully encompass the disease impact on the patient's QOL. A widely used and validated QOL instrument is the GO-QOL.31

Key Point 4.2.1: The physical and psychosocial impact of TED should be assessed for each patient, as it informs treatment decisions. When formal quantification of QOL is deemed appropriate, GO-QOL is the preferred instrument.

4.3. Formal ophthalmology evaluation

Ophthalmologists with expertise in TED can confirm the diagnosis and assess severity, activity, and disease trajectory to help plan management. Historical features portending a more severe TED course with diplopia or DON are listed in Table 2.36 A recent onset with rapidly worsening symptoms predicts aggressive disease, requiring expert evaluation, close follow-up, and prompt intervention.37

The directed ophthalmic examination uses standardized techniques to document how the orbit, eye, and eyelids are affected by TED.38 General ophthalmologists can assess vision, ocular motility, and the structures of the eye, and distinguish vision loss from various possible sources, including DON, corneal exposure, astigmatism, or choroidal folds. A subspecialist in oculoplastic and orbital disease will be able to differentiate TED from other orbital conditions, assess imaging, participate in medical management, and perform surgical interventions.

Table 3 organizes the functional and anatomic changes into four clinical categories (vision, soft tissue changes, impairment of ocular motility, and structural changes [proptosis and eyelid malposition]), and lists available ophthalmic techniques and ancillary tests used to assess them.39 For each finding the clinician must consider TED-related causes, non-TED-related causes, or both.

Table 3.

Formal Ophthalmic Examination for Thyroid Eye Disease Based on Vision, Inflammation, Strabismus, Appearance

Clinical ophthalmic examinationAncillary eye testsTED-associated mechanismsNon-TED-associated causesVision

Central vision

Color vision

Peripheral visionSnellen chart

Color plates

Pupil testing

Fundus examinationPattern visual evoked response

Optical coherence tomography (analyzes optic nerve for nerve fiber loss)

Visual field

Corneal topographyDON

Corneal exposure

Dry eye

Choroidal foldsCataract

Macular disease

Glaucoma

Diabetic retinopathyInflammation (soft tissue changes)

Redness and swelling of eyelids and conjunctivaSlit-lamp biomicroscopeClinical photographs

EUGOGOInflammation

Venous congestion

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (Fig. 2g)Allergic infective conjunctivitis

Iritis or scleritis

Dural cavernous fistula

Eyelid margin disease

Eyelid infection or neoplasia

Orbit neoplasia

Orbit inflammationStrabismus (ocular motility changes)

Diplopia

Ductions

StrabismusCorneal light reflex test

(Supplementary Fig. S1a, b)

Cover testingOrthoptics examination:

Perimetric ductions

Field of binocular single vision (area of binocular gaze with single image)

Fresnel prism

Prism measurementsExtraocular muscle restrictionMyasthenia gravis

Dural cavernous fistula

Orbital myositis

Orbital lymphoma

Orbital metastasis

IgG4 disease

Cranial nerve III, IV, VI palsyAppearance (structural changes)

Lid retractionRuler measure

Marginal reflex distance (the distance between the upper lid margin and the corneal reflex when the eye is in the primary position)Clinical photographsUpper lid retraction

Levator scarring

Compensatory levator

Retraction from restricted IR muscle

Lower lid retraction

From proptosis

From IR recession surgeryLid retraction from

Orbital fracture

Maxillary sinus atelectasis ProptosisExophthalmometry Fat expansion

Muscle enlargement

GC-induced lipogenesisOrbital neoplasia

Inflammation

Hemorrhage/trauma

GC-induced proptosis Corneal exposureSlit-lamp biomicroscope

Fluorescein stain Lid retraction

Lacrimal gland inflammationDry eyes

Corneal infection

Eyelid margin diseaseEUGOGO, European group on Graves' orbitopathy; GC, glucocorticoid; IR, inferior rectus.